The very first professional-level class I taught was at Mohawk College, back in 2004. There were 10 students the first class, and 8 of them were local to Hamilton. Local enough that they knew all about Ann’s Fabrics on Upper James Street. Ann’s has sparkly dance fabrics, laces, costume fabrics, and swimsuit fabric – all in quantities and designs like you have never seen. Three floors of spandex, in fact a valuable resource for anyone in the bespoke dance, swimsuit, or bodybuilding world. Our intrepid students spent thousands of dollars on spandex fabrics, thinking they would make beautiful, supportive, custom bras. Sadly, most of those fabrics ended up in a cupboard, never to be seen again. Don’t be like those first students!

For bra-making to be successful, you need three components that work together: cup fabric, band fabric, and the pattern. Of these, the cup fabric is the most important element of all, because we expect the cup to be supportive. Yes, we’ve all seen the bras or bralettes made of stretch lace or sports bras made of firm stretch fabrics. These are exceptions. The overwhelming majority of supportive bras in ready-to-wear use supportive knitted cup fabrics. But what does that mean?

Did you know that when the industry starts to make a bra pattern, a fabric with the qualities the designer is looking for has already been chosen, and the pattern drafter works with that alone? She does not make a pattern first, then go shopping for fabric that will work. The decision about the fabric is made first.

In the case of the bra-making enthusiast at home (that’s YOU!), it is the reverse of this. You likely have chosen the pattern, and now you want to choose the fabric. This is where the pattern maker’s recommendation comes in—read the pattern back to see what type of fabric is suggested. Chances are good that the suggested cup fabric is a knit with NO stretch or LOW stretch (often called “give” or mechanical stretch).

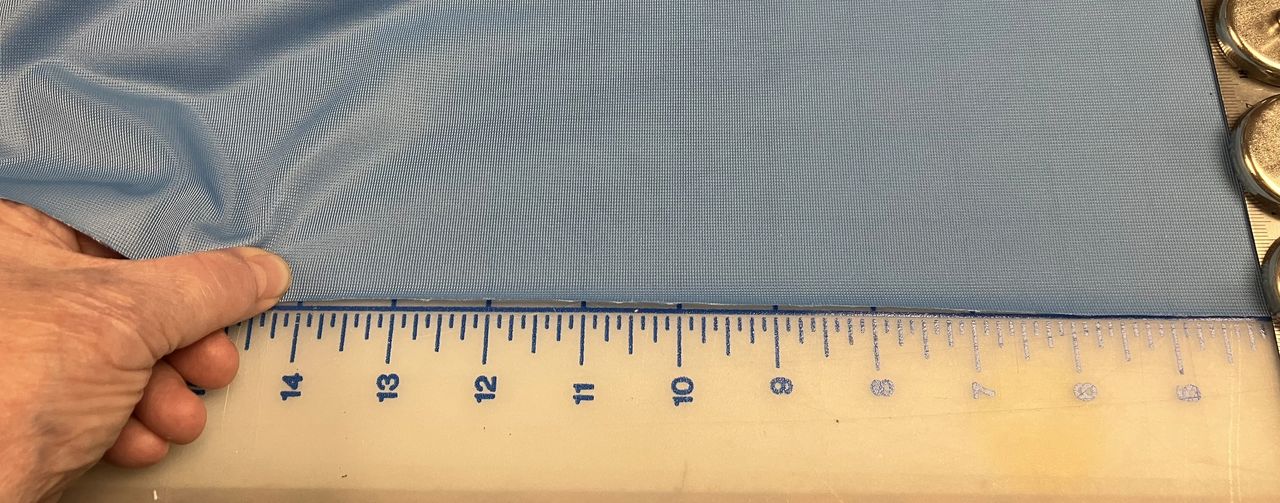

To determine the amount of stretch in a fabric, I like to pull it in both the lengthwise and the crosswise direction, then calculate the percentage of stretch. In the photo below, I measured between 4″ and 14″, a difference of 10 inches. The crosswise direction of the fabric stretched only .125″ (1/8″) over the original 10″. So the crosswise direction stretches only 1.25%, so it is virtually no-stretch. Most books recommend you use 4″ in your pull sample. I use 10″ on very low-stretch fabrics.

By comparison, the lengthwise direction stretched .5″ over the 10, making the stretch 5%. (On 10″ of fabric, move the decimal place one number to the right to find the percentage of stretch). In the case of Duoplex, the lengthwise direction of the fabric is the direction of greatest stretch. Pattern pieces should be placed on the fabric with this in mind.

I consider Duoplex a low-stretch fabric. You really want cup fabrics to have less than 7.5% stretch for the most supportive cups. If the fabric stretches more than this, you will have to make allowances for the fabric when drafting the pattern.

In the case of my students from 2004, their fabrics stretched 60-70% in both directions. Very suitable for swimwear and dance costumes, but not at all suitable for bra cups meant to be supportive.

In my next post, I’ll share the best cup fabrics I have used.